Guy Debord’s work is still very readable and relevant fifty years after it was written. The themes he addresses are still with us, arguably more so.

He begins the work with the following statement:

“In societies where modern conditions of production prevail, life is presented as an immense accumulation of spectacles. Everything that was directly lived has receded into a representation”.

(Chapter 1, section 1)

In a world where our understanding of the world is mediated by television, radio and the internet our own lives can seem insignificant. These media constantly present us with the grand narratives of the world; the economy, wars, famines, the lives of famous people. These presentations are curated to show the highlights, the spectacles which means we often know more about the lives of celebrities and politicians than we do about our own neighbours.

Debord’s work was originally intended as a critique of the rampant consumerism and creeping role of government in the 1960’s. The spectacles he refers to are the displays put on by government (political broadcasts, interviews, policy initiatives) and big business (advertising, trade shows, infomercials) to claim the high ground of our attention.

Perhaps the main change from the 1960’s to the present day is that the ability to create spectacle has filtered down to smaller agents of representation. Where once only government, big business and the church had the resources to put on convincing spectacles, the internet and social media provide anyone with the opportunity. Surely the highly curated Instagram accounts of influencers, the lavish websites of tiny business and the slavish posting of social media posts are all attempts at spectacle?

Debord’s ideas seem plausible, they echo not only Baudrillard’s ideas about hyperreality, but also our lived experiences of constant influencers, special offers, buy-one-get-one-free, festivals and exclusive opportunities. The consumer capitalist orthodoxy of contemporary life encourages us to regard these aspects of spectacle as the dominant, most important aspects of our lives.

Every so often, the consumers of the spectacle rise up in rebellion. Debord wrote during a time of revolt so it seems reasonable to look to him for insight. He was involved with the Situationist movement which specialised in creating situations which prompted a new perception of the existing order. These could be demonstrations and sit-ins, or less confrontational events like walking aimlessly through a city or subverting a map.

More specifically, how might a Debordian analysis assist a photographer in presenting their work?

Paris Biennale

In chapter 11, section 11, Debord states

“In analyzing the spectacle we are obliged to a certain extent to use the spectacle’s own language, in the sense that we have to operate on the methodological terrain of the society that expresses itself in the spectacle. For the spectacle is both the meaning and the agenda of our particular socio-economic formation”.

If we accept the idea of the spectacle, we should respond in terms of the spectacle. A recourse to logic is of little use if we acknowledge that we do operate in a society of the spectacle. That is the world we are in. The most obvious course open to us is to subvert this world. To understand this world and flip it upside down.

Many photographers regard the gallery exhibition as the validation they seek. This involves either gaining recognition and being invited to exhibit, placing your fate in the hands of critics, gallery owners or other gatekeepers. So let’s forget about gatekeepers, let’s forget about sales and previews and consider how we might create a situation in which we control the distribution of our work.

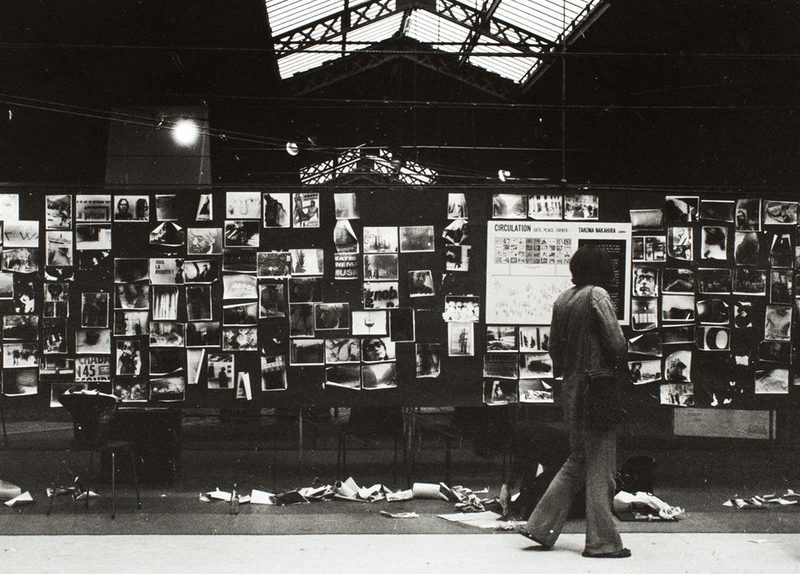

If we forget about sales, value is not an issue. We are also free to give away the work. I was inspired by the Japanese photographer Takuma Nakahira. When he participated in the 1971 Paris Biennale, he brought no prepared work. He went out each day and took pictures, then processed them and printed and glued the pictures to the walls of the Biennale. After the show he gave away the pictures. This completely overturns the idea of the precious and unique photographic art object.

https://www.artic.edu/exhibitions/2539/takuma-nakahira-circulation

The limited edition is a widely used tool in the art marketing world. Using the notion of a limited supply of any commodity is an accepted way of increasing the price. So giving away a limited edition is not only a powerful way of subverting the art market, but also drawing attention to what you are doing. By subverting the orthodox spectacles, this act becomes a spectacle in itself. It operates within the “methodological terrain of the society that expresses itself in the spectacle”.

Currently, I am working on the idea of a give-away limited edition of my work. As my work has a campaigning intent, the recipient would be offered the work, have the intent explained and be invited to visit a dedicated webpage. It would be interesting to check the visitor stats for the web page to see exactly how many recipients actually followed up to find out more about the work.

Paying for the production of work and then giving it away may seem counter-productive. But only if the notion (spectacle) of the art as commodity is accepted. If I pay for the production of prints, it is up to me what I do with them. They are my property, so their disposal is my choice. If I wish to defy the dominant notion of the art market and create a spectacle by distributing my work in a counter-intuitive way, I’m free to do so.

Featured image:

(Installation view of Circulation: Date, Place, Event, 1971. Takuma Nakahira. © Gen Nakahira).